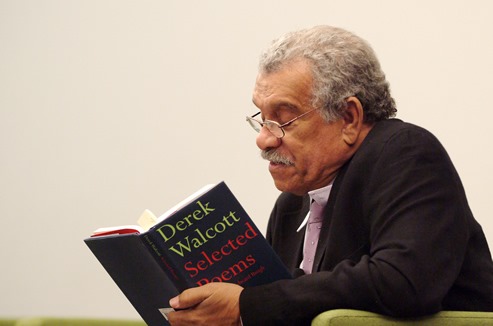

Un’elegia in sette movimenti ad apertura del libro omonimo, uscito nel 1997: il pianto per la morte della madre viene modulandosi intrecciando lutto privato, fede cristiana, natura tropicale e tradizione occidentale (Dante, Ovidio, la Bibbia, John Clare). Traduzione non d’autore per questi sette passi del premio Nobel per la letteratura 1992, in calce il testo originale.

Il dono

[per Alix Walcott]

i

Tra la visione dell’Ente del Turismo e il vero

Paradiso sta il deserto dove le esultanze di Isaia

forzano una rosa dalla sabbia. Il trentatreesimo canto

incide le nubi dell’alba con una luce concentrica,

l’albero del pane apre i palmi in lode del dono,

bois-pain, albero del pane, cibo degli schiavi, la beatitudine di John Clare,

strappato, errante Tom, accarezzatore di ermellini nella sua contea

di canne e grilli dei giunchi, che suona il violino all’aria umida,

allaccia gli stivali con le viti, guida scarabei vitrei

con i più teneri tocchi, cavaliere del maggiolino,

avvolto nelle nebbie delle contee, i loro campanili a chiocciola

palme aperte verso la pozza concava — ma la sua anima più salva

della nostra, benché torrenti di ferro gli incatenino le caviglie.

La brina gli imbianca la barba, sta nel guado

di un ruscello come il Battista che alza i rami per benedire

cattedrali e lumache, lo spezzarsi di questo nuovo giorno,

e le ombre della strada costiera presso cui giace mia madre,

con il traffico degli insetti che comunque va al lavoro.

La lucertola sul muro bianco fissa il geroglifico

della sua ombra di pietra, l’arceria frusciante delle palme,

le anime e le vele dei gabbiani in cerchio fanno rima con:

«In la sua volontà è nostra pace,»

Nella Sua volontà è la nostra pace. Pace nei porti bianchi,

nelle marine dove gli alberi maestri concordano, nei meloni a mezzaluna

lasciati tutta la notte in frigorifero, nelle fatiche egizie

delle formiche che spostano massi di zucchero, parole in questa frase,

ombra e luce, che vivono accanto come vicini,

e nelle sardine al pepe. Mia madre giace

vicino ai sassi bianchi della spiaggia, John Clare presso i mandorli di mare,

eppure il dono ritorna a ogni alba, con mia sorpresa,

con mia sorpresa e tradimento, sì, entrambi insieme.

Mi commuovo come te, pazzo Tom, per una fila di formiche;

ne guardo l’operosità e sono giganti.

ii

Là sulla spiaggia, nel deserto, giace il pozzo oscuro

dove fu calata la rosa della mia vita, vicino alle piante scosse,

vicino a una pozza di lacrime fresche, scandite dalla campana dorata

dell’allamanda, dalle spine della bougainvillea, ed è questo

il loro dono! Brillano di sfida tra erbaccia e fiore,

anche quelle che prosperano altrove, veccia, edera, clematide,

su cui ora il sole sorge con tutta la sua forza,

non per l’Ente del Turismo né per Dante Alighieri,

ma perché non c’è altra via che la sua ruota possa prendere

se non rendere i solchi della strada costiera un’allegoria

della carriera di questa poesia, della tua, che lei morì per il bene

di una corona d’alloro falso; così, John Clare, perdonami,

per il bene di questo mattino, perdonami, caffè, e perdonami,

latte con due bustine di zucchero artificiale,

mentre guardo crescere questi versi e l’arte della poesia indurirmi

in un dolore misurato come questo, per tracciare la figura velata

di Mamma che entra nell’elegiaco standard.

No, c’è il lutto, ci sarà sempre, ma non deve far impazzire,

come Clare, che pianse la perdita di uno scarabeo, per il peso

del mondo in una goccia di rugiada su clematide o veccia,

e il fuoco in questi versi secchi come esca di questa poesia che odio

quanto amo lei, povera creatura battuta dalla pioggia,

redentrice dei topi, conte del condannato protettorato

di cavalleria sotto il tuo mantello; su, basta ora!

iii

Dono!

Nei campanelli delle rane arboricole con il loro clamore costante

nell’indaco buio prima dell’alba, il morse che svanisce

di lucciole e grilli, poi la luce sull’armatura dello scarabeo,

e su quella del rospo, presagi tardivi, ortiche del rimorso

che germoglieranno dalla sua tomba per lo strazio della vanga.

E tuttavia non averla amata abbastanza è amare di più,

se lo confesso, e lo confesso. Il rivolo delle sorgenti sotterranee,

il borbottio dei burroni gonfi sotto felci fradicie,

che allentano la presa delle loro radici, finché le zolle villose

come pugni che si aprono vorticano dove il burrone le gira,

e il brivido del dopo piega le canne selvatiche.

Dono nella furia mattutina delle formiche,

nella cappella della lumaca che si muove sotto gli ignami selvatici,

lode nel decomporsi e nel processo, stupore nell’ordinario,

nel vento che legge le linee dei palmi dell’albero del pane,

nel sole contenuto in un globo di rugiada cristallina,

dono nella continuità delle formiche che tracciano una linea di farina cruda,

misericordia per la mangusta che sguscia davanti alla mia porta,

nel parallelogramma di luce steso sul pavimento della cucina,

poiché Tuo è il Regno, la Gloria e la Potenza,

le campane di Saint Clement nei calenduli sull’altare,

nelle spine della bougainvillea, nel lillà imperiale

e nelle palme piumate che annuivano all’ingresso

in Gerusalemme, il peso del mondo sul dorso

di un asino; smontando, Egli lasciò lì la sua croce come sentinella

e per il centurione ghignante; allora credetti nella Sua Parola,

in un marito immacolato per una vedova, nei banchi di legno scuro,

quando la campana della cappella radunava la nostra mandria

nelle stalle verniciate, nei cui innari fruscianti udii

le fresche sorgenti giacobee, il mormorio che Clare udì

del dono che permane, il linguaggio limpido che lei ci insegnò,

«come la cerva anela», a questo le sue orecchie acute si drizzavano

mentre i suoi tre cerbiatti brucavano le acque che rinnovano l’anima,

«come la cerva anela ai rivi d’acqua», che appartenevano

alla lingua in cui ora la piango, o quando

le mostrai la mia prima elegia, quella per suo marito, e poi la sua.

iv

Ma può o non può leggerlo? Puoi leggerlo,

Mamma, o sentirlo? Se salissi sul pulpito, predicatore laico

come il tenero Clare, come il povero Tom, così che guarda, Signorina!

le formiche vengono a te come bambini, alla loro amata maestra

Alix, ma a differenza della recitazione silenziosa degli infanti,

del coro che Clare e Tom udivano nella loro contea piovosa,

noi non abbiamo consolazione se non l’enunciazione, da cui questo grido selvaggio.

Le lumache entrano in porto, le piante dell’albero del pane sulla Bounty

saranno issate a bordo, e il Dio bianco è il capitano Bligh.

Sull’erba piumosa e bianca delle tombe passa l’ombra dell’anima,

la tela si squarcia sugli alberi di crocette della Bounty,

e gli alisei sollevano i sudari della vela risorta.

Tutti si muovono nel loro passaggio verso la stessa madrepatria,

la donnola che graffia la terra, il gufo cieco o la foca al sole.

La fede si fa ammutinata. Il corpo costolato con il suo carico

si arresta nella bonaccia, il Dio-capitano è gettato alla deriva

da un cristiano ammutinato, nella scia dell’Argo che vira

le piante dondolano nei solchi dell’oceano, i germogli salgono e scendono,

e l’Australia dell’anima è come il Nuovo Testamento

dopo il Vecchio Mondo, il codice dell’occhio per occhio;

l’orizzonte gira lentamente e l’argomento dell’Autorità

si indebolisce, nella scialuppa con il capitano Bligh.

Questa fu una delle tue prime lezioni, come il Figlio-Cristo

interroga il Padre, per stabilirsi su un’altra isola, infestata da Lui,

dal punto di una divinità furente sull’orizzonte rigato,

che si riduce in senso e distanza, diventando più fioca:

tutti questi passaggi prevedibili che prima disobbediamo

prima di diventare ciò che sfidammo; ma tu non mutasti mai

la tua voce, né sospirando né cucendo, pregavi

ad alta voce tuo marito, pedalando gli inni che tutti udivamo

nei banchi verniciati: «C’è un verde colle lontano»,

«Gerusalemme la dorata». La tua melodia vacillava

ma mai la tua fede nel dono che è la Sua Parola.

v

Tutte queste onde crepitano dalla cultura di Ovidio,

le sue sibilanti e consonanti; un metro universale

accumula queste firme come iscrizioni di alghe marine

che seccano nel sole acre, versi rigati da mitra

e alloro, o spruzzi che rapidamente incoronano la fronte

di uno scoglio (e spero che questo chiuda la questione

delle presenze). Nessuna anima è mai stata inventata,

eppure ogni presenza è trasparente; se la incontrassi

(in camicia da notte, a piedi nudi, canticchiando verso i bassifondi),

dovrei chiamare la sua ombra quella di un disegno inventato

dal progetto greco-romano, colonne d’ombre

gettate dal Foro, prospettive augustee —

pioppi, colonnati di casuarine, la luce che entra ed esce dai mandorli

fatti di latino originario, nessuna foglia se non l’olivo?

Questioni di intonazione. Di fronte a una radiosità serafica

(non interrompere!), i mortali si strofinano gli occhi scettici

che l’inferno sia un fuoco di spiaggia notturno dove danzano le braci,

con lucciole temporali come pensieri del Paradiso;

ma esistono istinti inspiegabili che continuano a tornare

non solo da speranza o paura, reali come pietre,

i volti dei morti che attendiamo mentre le formiche trasferiscono

le loro città, anche se non crediamo più negli splendenti.

Mi aspetto a metà di non vederti più, poi più che a metà,

quasi mai, o mai poi — eccolo, l’ho detto —

ma ho sentito qualcosa di meno che finale al margine della tua tomba,

qualcos’altro da qualche parte, ugualmente temuto,

poiché il timore dell’infinito è lo stesso della morte,

luce insopportabile, la sostanza che teme

la propria sostanza, dissolvendosi in gas e vapori,

come il nostro timore della distanza; abbiamo bisogno di un orizzonte,

una linea di divisione che renda le stelle vicine

anche se l’infinito le separa, possiamo pensare a un solo sole:

tutto ciò che dico è che il timore della morte è nei volti

che amiamo, il timore del nostro morire, o del loro;

perciò vediamo nel luccichio di spazi incommensurabili

non stelle o braci cadenti, non meteore, ma lacrime.

vi

I manghi frusciano serenamente quando sono in fiore,

nessuno conosce il nome di quel cedro loquace

i cui fiori a campana cadono, il pomme-arac viola il suolo.

Le colline azzurre nel tardo pomeriggio sembrano sempre più tristi.

La notte della campagna in attesa fuori dalla porta;

la lucciola continua ad accendere fiammiferi, e il fianco della collina fuma

di un segnale azzurrastro di carbone, poi il fumo brucia

in una domanda più grande, che si forma e si disfa,

poi si perde in una nuvola, finché la domanda ritorna.

Secchi sbattono sotto i tubi, i villaggi iniziano agli angoli.

Un uomo e il suo cane al trotto tornano dall’orto.

Il mare arde oltre i tetti arrugginiti, il buio è su di noi

prima che ce ne accorgiamo. La terra odora di ciò che è stato fatto,

i piccoli cortili si illuminano, il giorno muore e i suoi dolenti

cominciano, la prima corona di moscerini; era allora che ci sedevamo

su verande luminose a guardare morire le colline. Nulla è banale

una volta che i cari sono scomparsi; vestiti vuoti in fila,

ma forse la nostra tristezza stanca chi amava la gioia;

non solo sono liberati dal nostro dolore consueto,

sono senza fame, senza alcun appetito,

ma fanno parte della furia vegetale della terra; le loro vene crescono

con il mammi-apple selvatico, l’albero del pane dalle mani aperte,

il loro cuore nel melograno aperto, nell’avocado tagliato;

le tortore beccano dai loro palmi; le formiche portano il carico

della loro dolcezza, la loro assenza in tutto ciò che mangiamo,

il loro sapore che addolcisce tutti i nostri succhi molteplici,

la loro fede che spezziamo e mastichiamo in uno spicchio di manioca,

ed ecco qui il primo stupore: che la terra gioisca

nel mezzo della nostra agonia, la terra che l’avrà

per sempre: il vento lucida le pietre bianche e le voci delle secche.

vii

In primavera, dopo l’auto-sepoltura dell’orso, la balbuzie

dei crochi si apre e canta in coro, i ghiacciai si ritirano e si sciolgono,

gli stagni gelati si spezzano in mappe, lance verdi balzano

dai campi che si sciolgono, bandiere di corvi si alzano e lacerano

la luce trafitta, le valanghe silenziose che crollano

di un cielo instabile; l’arvicola si svolge e la lontra

spinge la testa lucida tra i rami della scarpata;

anfratti, tombini e ruscelli ruggiscono con acqua che intorpidisce i polsi.

I cervi scavalcano ostacoli invisibili e fiutano l’aria tagliente,

gli scoiattoli balzano come domande, le bacche arrossiscono facilmente,

i margini gioiscono delle proprie forme (chiunque sia il loro artefice).

Ma qui c’è una sola stagione, il nostro Eden viridiano

è quello del giardino primordiale che generò la decomposizione,

dal seme di una scheggia di scarabeo o di una lepre morta

bianca e dimenticata come l’inverno con la primavera in arrivo.

Non c’è più mutamento ora, né cicli di primavera, autunno, inverno,

né l’estate perpetua di un’isola; lei portò via il tempo con sé;

nessun clima, nessun calendario se non questo giorno generoso.

Come il povero Tom diede la sua ultima crosta agli uccelli tremanti,

come tra canne e pozze fredde John Clare benedisse questi musicisti esili,

che le formiche mi insegnino ancora con le lunghe linee delle parole,

il mio mestiere e dovere, la lezione che insegnasti ai tuoi figli,

scrivere della luce come dono sulle cose familiari

che stanno sul punto di tradursi da sole in notizia:

il granchio, la fregata che galleggia con ali cruciformi,

e quell’albero inchiodato e trafitto di spine che apre i suoi banchi

al merlo che non l’ha dimenticata, perché canta.

The Bounty

[for Alix Walcott]

i

Between the vision of the Tourist Board and the true

Paradise lies the desert where Isaiah’s elations

force a rose from the sand. The thirty-third canto

cores the dawn clouds with concentric radiance,

the breadfruit opens its palms in praise of the bounty,

bois-pain, tree of bread, slave food, the bliss of John Clare,

torn, wandering Tom, stoat-stroker in his county

of reeds and stalk-crickets, fiddling the dank air,

lacing his boots with vines, steering glazed beetles

with the tenderest prods, knight of the cockchafer,

wrapped in the mists of shires, their snail-horned steeples

palms opening to the cupped pool—but his soul safer

than ours, though iron streams fetter his ankles.

Frost whitening his stubble, he stands in the ford

of a brook like the Baptist lifting his branches to bless

cathedrals and snails, the breaking of this new day,

and the shadows of the beach road near which my mother lies,

with the traffic of insects going to work anyway.

The lizard on the white wall fixed on the hieroglyph

of its stone shadow, the palms’ rustling archery,

the souls and sails of circling gulls rhyme with:

“In la sua volont è nostra pace,”

In His will is our peace. Peace in white harbours,

in marinas whose masts agree, in crescent melons

left all night in the fridge, in the Egyptian labours

of ants moving boulders of sugar, words in this sentence,

shadow and light, who live next door like neighbours,

and in sardines with pepper sauce. My mother lies

near the white beach stones, John Clare near the sea-almonds,

yet the bounty returns each daybreak, to my surprise,

to my surprise and betrayal, yes, both at once.

I am moved like you, mad Tom, by a line of ants;

I behold their industry and they are giants.

ii

There on the beach, in the desert, lies the dark well

where the rose of my life was lowered, near the shaken plants,

near a pool of fresh tears, tolled by the golden bell

of allamanda, thorns of the bougainvillea, and that is

their bounty! They shine with defiance from weed and flower,

even those that flourish elsewhere, vetch, ivy, clematis,

on whom the sun now rises with all its power,

not for the Tourist Board or for Dante Alighieri,

but because there is no other path for its wheel to take

except to make the ruts of the beach road an allegory

of this poem’s career, of yours, that she died for the sake

of a crowning wreath of false laurel; so, John Clare, forgive me,

for this morning’s sake, forgive me, coffee, and pardon me,

milk with two packets of artificial sugar,

as I watch these lines grow and the art of poetry harden me

into sorrow as measured as this, to draw the veiled figure

of Mamma entering the standard elegiac.

No, there is grief, there will always be, but it must not madden,

like Clare, who wept for a beetle’s loss, for the weight

of the world in a bead of dew on clematis or vetch,

and the fire in these tinder-dry lines of this poem I hate

as much as I love her, poor rain-beaten wretch,

redeemer of mice, earl of the doomed protectorate

of cavalry under your cloak; come on now, enough!

iii

Bounty!

In the bells of tree-frogs with their steady clamour

in the indigo dark before dawn, the fading morse

of fireflies and crickets, then light on the beetle’s armour,

and the toad’s too-late presages, nettles of remorse

that shall spring from her grave from the spade’s heartbreak.

And yet not to have loved her enough is to love more,

if I confess it, and I confess it. The trickle of underground

springs, the babble of swollen gulches under drenched ferns,

loosening the grip of their roots, till their hairy clods

like unclenching fists swirl wherever the gulch turns

them, and the shuddering aftermath bends the rods

of wild cane. Bounty in the ant’s waking fury,

in the snail’s chapel stirring under wild yams,

praise in decay and process, awe in the ordinary

in wind that reads the lines of the breadfruit’s palms

in the sun contained in a globe of the crystal dew,

bounty in the ants’ continuing a line of raw flour,

mercy on the mongoose scuttling past my door,

in the light’s parallelogram laid on the kitchen floor,

for Thine is the Kingdom, the Glory, and the Power,

the bells of Saint Clement’s in the marigolds on the altar,

in the bougainvillea’s thorns, in the imperial lilac

and the feathery palms that nodded at the entry

into Jerusalem, the weight of the world on the back

of an ass; dismounting, He left His cross there for sentry

and sneering centurion; then I believed in His Word,

in a widow’s immaculate husband, in pews of brown wood,

when the cattle-bell of the chapel summoned our herd

into the varnished stalls, in whose rustling hymnals I heard

the fresh Jacobean springs, the murmur Clare heard

of bounty abiding, the clear language she taught us,

“as the hart panteth,” at this, her keen ears pronged

while her three fawns nibbled the soul-freshening waters,

“as the hart panteth for the water-brooks” that belonged

to the language in which I mourn her now, or when

I showed her my first elegy, her husband’s, and then her own.

iv

But can she or can she not read this? Can you read this,

Mamma, or hear it? If I took the pulpit, lay-preacher

like tender Clare, like poor Tom, so that look, Miss!

the ants come to you like children, their beloved teacher

Alix, but unlike the silent recitation of the infants,

the choir that Clare and Tom heard in their rainy county,

we have no solace but utterance, hence this wild cry.

Snails move into harbour, the breadfruit plants on the Bounty

will be heaved aboard, and the white God is Captain Bligh.

Across white feathery grave-grass the shadow of the soul

passes, the canvas cracks open on the cross-trees of the Bounty,

and the Trades lift the shrouds of the resurrected sail.

All move in their passage to the same mother-country,

the dirt-clawing weasel, the blank owl or sunning seal.

Faith grows mutinous. The ribbed body with its cargo

stalls in its doldrums, the God-captain is cast adrift

by a mutinous Christian, in the wake of the turning Argo

plants bob in the ocean’s furrows, their shoots dip and lift,

and the soul’s Australia is like the New Testament

after the Old World, the code of an eye for an eye;

the horizon spins slowly and Authority’s argument

diminishes in power, in the longboat with Captain Bligh.

This was one of your earliest lessons, how the Christ-Son

questions the Father, to settle on another island, haunted by Him,

by the speck of a raging deity on the ruled horizon,

diminishing in meaning and distance, growing more dim:

all these predictable passages that we first disobey

before we become what we challenged; but you never altered

your voice, either sighing or sewing, you would pray

to your husband aloud, pedalling the hymns we all heard

in the varnished pew: “There Is a Green Hill Far Away,”

“Jerusalem the Golden.” Your melody faltered

but never your faith in the bounty which is His Word.

v

All of these waves crepitate from the culture of Ovid,

its sibilants and consonants; a universal metre

piles up these signatures like inscriptions of seaweed

that dry in the pungent sun, lines ruled by mitre

and laurel, or spray swiftly garlanding the forehead

of an outcrop (and I hope this settles the matter

of presences). No soul was ever invented,

yet every presence is transparent; if I met her

(in her nightdress ankling barefoot, crooning to the shallows),

should I call her shadow that of a pattern invented

by Graeco-Roman design, columns of shadows

cast by the Forum, Augustan perspectives—

poplars, casuarina-colonnades, the in-and-out light of almonds

made from original Latin, no leaf but the olive’s?

Questions of pitch. Faced with seraphic radiance

(don’t interrupt!), mortals rub their skeptical eyes

that hell is a beach-fire at night where embers dance,

with temporal fireflies like thoughts of Paradise;

but there are inexplicable instincts that keep recurring

not from hope or fear only, that are real as stones,

the faces of the dead we wait for as ants are transferring

their cities, though we no longer believe in the shining ones.

I half-expect to see you no longer, then more than half,

almost never, or never then—there I have said it—

but felt something less than final at the edge of your grave,

some other something somewhere, equally dreaded,

since the fear of the infinite is the same as death,

unendurable brightness, the substantial dreading

its own substance, dissolving to gases and vapours,

like our dread of distance; we need a horizon,

a dividing line that turns the stars into neighbours

though infinity separates them, we can think of only one sun:

all I am saying is that the dread of death is in the faces

we love, the dread of our dying, or theirs;

therefore we see in the glint of immeasurable spaces

not stars or falling embers, not meteors, but tears.

vi

The mango trees serenely rust when they are in flower,

nobody knows the name for that voluble cedar

whose bell-flowers fall, the pomme-arac purples its floor.

The blue hills in late afternoon always look sadder.

The country night waiting to come in outside the door;

the firefly keeps striking matches, and the hillside fumes

with a bluish signal of charcoal, then the smoke burns

into a larger question, one that forms and unforms,

then loses itself in a cloud, till the question returns.

Buckets clatter under pipes, villages begin at corners.

A man and his trotting dog come back from their garden.

The sea blazes beyond the rust roofs, dark is on us

before we know it. The earth smells of what’s done,

small yards brighten, day dies and its mourners

begin, the first wreath of gnats; this was when we sat down

on bright verandahs watching the hills die. Nothing is trite

once the beloved have vanished; empty clothes in a row,

but perhaps our sadness tires them who cherished delight;

not only are they relieved of our customary sorrow,

they are without hunger, without any appetite,

but are part of earth’s vegetal fury; their veins grow

with the wild mammy-apple, the open-handed breadfruit,

their heart in the open pomegranate, in the sliced avocado;

ground-doves pick from their palms; ants carry the freight

of their sweetness, their absence in all that we eat,

their savour that sweetens all of our multiple juices,

their faith that we break and chew in a wedge of cassava,

and here at first is the astonishment: that earth rejoices

in the middle of our agony, earth that will have her

for good: wind shines white stones and the shallows’ voices.

vii

In spring, after the bear’s self-burial, the stuttering

crocuses open and choir, glaciers shelve and thaw,

frozen ponds crack into maps, green lances spring

from the melting fields, flags of rooks rise and tatter

the pierced light, the crumbling quiet avalanches

of an unsteady sky; the vole uncoils and the otter

worries his sleek head through the verge’s branches;

crannies, culverts, and creeks roar with wrist-numbing water.

Deer vault invisible hurdles and sniff the sharp air,

squirrels spring up like questions, berries easily redden,

edges delight in their own shapes (whoever their shaper).

But here there is one season, our viridian Eden

is that of the primal garden that engendered decay,

from the seed of a beetle’s shard or a dead hare

white and forgotten as winter with spring on its way.

There is no change now, no cycles of spring, autumn, winter,

nor an island’s perpetual summer; she took time with her;

no climate, no calendar except for this bountiful day.

As poor Tom fed his last crust to trembling birds,

as by reeds and cold pools John Clare blest these thin musicians,

let the ants teach me again with the long lines of words,

my business and duty, the lesson you taught your sons,

to write of the light’s bounty on familiar things

that stand on the verge of translating themselves into news:

the crab, the frigate that floats on cruciform wings,

and that nailed and thorn riddled tree that opens its pews

to the blackbird that hasn’t forgotten her because it sings.

Scopri di più da Giuseppe Genna

Abbonati per ricevere gli ultimi articoli inviati alla tua e-mail.